SPECIAL REPORT: Sparkle City’s Opioid Epidemic

In 2013, Terry Hanley lost his stepson Zachary Spaulding to a heroin overdose. Spaulding was 27. In 2015, here in Midland, he watched four more kids whom he had coached in different sports die of overdoses within the span of about two months.

“That was when I knew I needed to do something,” Hanley tells the City Paper. “I was already a part of a coalition group that the Legacy Center had started. And to me it was getting more and more that it was just a group of people that got together once a month and wanted to talk and feel good about themselves and never do anything. And it was driving me nuts.”

Hanley, who owns a small business here in town, Hanley’s Custom Sports, had a visit from Lori Wood and a couple of her friends who were looking to order some t-shirts. Hanley and Wood started talking and he found out that she ran a nonprofit called For A Brighter Tomorrow, and it all started clicking: they were in the same boat.

“The nice part is that it gave me a group to use as a backing to want to go do things. We did an awareness event outside of the courthouse right away, just to kind of wake Midland up,” he says. “We made up a big banner that read ‘heroin is killing our community’ and we sat out there on the corner of Main [St.] and M-20 for four hours just because we wanted to start waking people up and start getting rid of the stigma in Midland.”

They followed that by holding four summits in the community, he says. They also did a couple of events out at a church on Poseyville, with vendors so that people could get information about anything they needed concerning abuse and overdose.

“It kind of helped by pushing other people more, the nice part is that it gave the Legacy Center the push to start doing more and to me it’s just amazing in our community that after three years, how much has changed and how much is being done to help fight this now,” he says. “That’s kind of the part I love is just sitting back and looking and saying you know, we finally are there to where the stigma is starting to be gone but it’s also where there’s just so many people getting involved in this and doing things now. Different groups, hospitals, doctors, everything is just starting to roll together now and that makes me really happy to see.”

Hanley had known his stepson, Zachary, since he was seven years old. He says Spaulding started smoking marijuana in middle school, and high school was really tough for him.

“He was a big kid, even in middle school, just a big kid. And he just couldn’t find happiness in school. It was hard for him to study or do anything, and people always pushed sports on him and he didn’t really get into it,” Hanley says. “So he dropped out of high school when he turned 18, and just kind of went to work and did some things. He got arrested when he was 24, in Saginaw and it was for possession of drug paraphernalia. And that was when we first found out that he had been using heroin. I mean, we knew that he had smoked pot, and our feeling was as long as it didn’t get out of control… well then we found out he was doing heroin, and he went to jail for six months.”

Hanley says that to him, heroin was a street drug he was aware of growing up in Detroit in the 70s, but other than that, he didn’t really know a lot about it.

Spaulding would be on and off the drug for about three or four years that Hanley was aware of, and he would go and live with different friends until they realized his habits, and then they’d kick him out too.

“It was a lot of hard times for him, but for me at the time it was ‘well, just quit.’ You know, I didn’t realize that that wasn’t the case. Until now, I mean now I know,” he says. “So he kept using, but ended up going back and getting his GED, and he ended up with a real good job with a welding company in Saginaw the August before he died.”

Spaulding’s grandfather owned a house in Midland, and he would go to Florida every year, so Spaulding would live there rent free while he was working, Hanley explains.

“That was a mistake on our part, looking back now,” he says. “Because he didn’t have any rent to pay, so we didn’t have any signs to know when he was in trouble… so he moved in there and everything was going good, and then the last time I saw him was Christmas Day. And he was working nights so he would always call his mom when he got out of work and she was going into work, they would always talk. The Monday after he died, she didn’t get a phone call from him and she thought that was kind of weird, so she left him a couple messages, then Tuesday, the same thing.”

They decided to bring him dinner that night, then as they were pulling out of the driveway, they got the call from a detective.

“They had told us that he had passed, and that actually he had passed two days prior and he had been sitting in the house for two days dead. And his uncle found him when he came in to get mail,” says Hanley. “So we never got to see him, never got closure, and that’s one of the hardest parts.”

Hanley says Spaulding had gone up to see his father in Traverse City on Saturday, came home on Sunday, and for some reason he called in sick on Sunday night and had a girl with him.

“We knew who she was, she still won’t talk to us,” he says. “So we think that, somehow she talked him into getting high again. They found him with the needle still in his arm … and you know, your life is just completely changed from that point on. Because it’s always the ‘what-ifs’ and now I’ve just learned so much. I have friends that have children who are addicted to heroin and they don’t talk to you because they’re afraid of the stigma. But I just want your kid to live, I don’t want you to go through what we’re going through, so I do a lot of counseling with kids and parents. And we’re up to 19 parents who have lost children in our group that we stay very close to and talk to all the time and we’re there for.”

Hanley says that for awhile they used to really push to try to talk to the girl, but then she went to prison. He says he holds no regrets towards her and he understands that it was Spaulding’s choice to put the needle in his arm, but it still would’ve been nice to have some sort of closure by simply knowing what exactly happened that night.

“It was Jan. 22, 2013. Five minutes after five. And I remember everything about it as if it happened yesterday,” he says. “When I go and talk to kids in school, I can define the next four hours of that night vividly. And then go into a blank for the next three days and survive everything and try to put it away. I would not let my wife go into depression, and we had a really nice couple that stayed with us, and I could go to their house and cry because I told myself I won’t break down in front of my wife because that would just make her worse.”

He says they just kept busy, doing something every night with their friends, going to the gym, out to dinner, and his wife is finally speaking in front of people about it.

“That’s a big step for a mom, it really is. To get a mom out there to speak is awesome,” he says. “It takes a lot.”

Hanley speaks at local schools to raise awareness but he also says that For A Brighter Tomorrow also raises money to help recovering addicts.

“We’re set up to give them 90 days of help where we pay 50 percent of their drug testing, and 50 percent of their drug counseling. We offer clothing, we offer household items, we have volunteers that put together baggies of goodies, we offer coupons for clothes to help so that if they’re going to go get an interview and they need to go to one of the thrift shops, we have coupons for there,” he says.

He says they limit their help to 90 days because their philosophy is that if it’s any more than that, they feel that they’re enabling them. And people should be able to get on their feet within that time frame.

* * *

Aleisha Shobe is the mother of two healthy, athletic and academically gifted boys, 12 and 13 years old now. She earned degrees in both nursing and business management – neither of which she is allowed to work under. But she is an addict who has managed to save herself. And since 2011, she says she’s been clean of any hard drugs.

In the last year, however, she’s been unable to hold down a job. She’s had short stints at Café Zinc, McDonald’s and Dollar Tree. She says she’s been let go from all of them because of seizures.

This article has been updated to more accurately portray Ms. Shobe’s former places of employment.

In 2003, when she was diagnosed with a chemical imbalance in her brain, she started self-medicating.

“That’s when I became a heroin addict,” she tells the City Paper.

“I think [the seizures] are a result of usage and abusive relationships,” says Shobe. “Because it wasn’t just heroin… I mean, when you can’t find heroin, you go to anything.”

Shobe says the underlying health issues aren’t the only result of her past drug use. With the support of her parents and boyfriend, Joseph, she gets a lot of help with her boys, helping to shuttle them around to school events and paying her leftover court costs. Until those fines are paid off, she says she’ll remain on probation, and her felonies will stay on her record until then as well.

“I’m a felon. And the community looks down on you, a community where you were once looked at as a good person,” she says. “I mean, I once was held at high standards in this community, and now people just look at you like you’re nothing.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Shobe says she has convictions for four forgeries, nine gun charges, and eighteen aggravated assault charges as a result of her drug abuse.

“I grew up going to church. Elementary school through almost middle school, I went to a private Christian school. I wore skirts all the way past my knees up until I first tried [heroin],” she says. “I was that nerd. President of the book club and drama club, you know, Volunteen of the year … so, that into a massive drug habit. But when you’re told have a chemical imbalance and you have to take a handful of pills just to be able to handle life now. And then life just kind of progresses, and you stick a needle in your arm to help it, and then the next thing you know you’re so far into it.”

She recently moved back from Pensacola, Fla. about two years ago. She and her family originally left the area because she says it was very difficult for a felon to find work in the area.

“Especially in Midland. There’s just a very high stigma,” she says.

She says her first encounter with hard drugs was when she worked in the mall, and she had met her future ex-husband. He had just gotten out of prison, but she thought he was cute. Then she found out he lived down the street from her. He still had a girlfriend at the time. Then one day after work, they hung out with a group of friends, and someone broke out a few different things, and everyone started trying what was there. It was as casual as that.

That’s how scary it was and how mundane the whole situation seemed. She says over the years, she overdosed multiple times on heroin, and had to be brought back by paramedics with Narcan.

“Now I can joke about it, but it wasn’t funny back then,” she says.

Shobe says she’s tried just about everything, but her drug of choice was mainly heroin. “Meth, crack and coke made me awake… I was awake and aware of everything. Heroin is a downer. You are unaware of anything going on around you. You don’t have to think about your failures in life, or anything. But when you’re on the uppers, you notice everything that’s going on around you. You notice every little nook and cranny. Everything that’s dirty, everything that’s clean… ‘oh, I messed up on that eyelash, I’ve got to wipe my whole face off and fix it!’ But when you’re on downers, you don’t give a fuck about anything. And that’s what I wanted.”

“Imagine yourself just nodding out and drooling on yourself. That’s what it feels like. When you’re so depressed and lost within yourself, then that’s exactly what you want.”

Shobe says that she’s tried every method of usage, from snorting it to smoking it, to shooting it. She says the veins in her arms are shot because of her usage, so she started shooting it into a vein underneath her eye or into the artery in her neck.

She says she feels incredibly lucky to be alive. After doing heroin, every day, all day long, for nine years, including the year and two months she did in County – she has a lot to be thankful for. That’s nine years of use. And now nine years of being clean.

“I was getting sentenced by [former Midland County District] Judge [Jon] Lauderbach [in 2011] and he had actually given me a prison sentence. And the day I thought I was going to ride out to prison, he actually pulled me back into his courtroom,” she says. “And he said, ‘well, are you ready to give this another shot?’ and I thought, what are you talking about? ‘Like, the sobriety thing, because I know you can do it.’ And I said, I guess I’ve got no other choice because I’m riding out to prison. And he said, ‘no you’re not.’ I was lost. The next thing I know, my mom is walking in. And that was the day he gave me a lifetime no contact order with my ex-husband, Ronnie [the father of both of her boys]. He told my mom to get me out there, take me home, get me sober… and I had another six years of probation. And I got off of probation in two and a half.”

Jon Lauderbach is a donor to the City Paper. Please read our Editorial Independence policy to see how our sponsors, donors, and advertisers never influence our journalism.

“My mom knew it wasn’t going to be easy. But he wanted to see me back in his courtroom next week. And I looked like Hell. I walked into his courtroom in PJ’s. Because I was not detoxing very well,” she says. “He and [Midland County Circuit Court] Judge [Michael J.] Beale had known me. Judge Beale and [Midland County District Court] Judge [Stephen P.] Carras were the ones that had given me Volunteen of the Year … and they had came and seen me in National Honor Society my junior and senior years. I mean he had known, seen my face before and knew who I was. All of these judges who were involved in my sentencing(s), knew who I was. It was just hard for them to see me go down this road.”

She says she then had to go to J&A Counseling and Evaluation Services, a series of drug counseling sessions, as well as be drug tested three times a week at J&A as well as two times a week at her probation office. She had to go through both a mouth swab and urine tests and was prohibited from having anything in her system.

Since Judge Lauderbach didn’t really have faith in the rehabilitation centers in the state at the time, he didn’t send her to any of those, she says. According to Shobe, the Sunrise Recovery Center had just been temporarily closed because employees were caught giving drugs to patients. All of this forced her to get clean the old fashion way – cold turkey.

“I know this is going to sound very judgmental, so forgive me,” she says. “But I think that it’s just another reason to stay high. Methadone and Suboxone, I don’t think they really help you at all, because I’ve tried them. They give you the same feeling as the heroin.”

When asked why would anyone want that, she says that those medicines are supposed to make you ill if you try heroin while on them. So quitting cold was the way for her. She says she made it through by just sleeping a lot, eating a lot of chicken broth, drinking a lot of juices and just going through the pain.

“Honestly, it took me about a year. Every day was a battle. And still, it’s a constant struggle. I smoked anywhere from 3-4 packs of cigarettes a day. And now I’m just finally getting down to barely a pack a day,” she says. “So far I haven’t had anything that has triggered it [a relapse], I mean I have really bad and depressive days, but mainly it’s because financially I can’t support my kids. But nothing really is worth me going back to that.”

“I just really think that our community needs to take their blinders off. The epidemic isn’t going to go away no matter how bad we want it to,” she says. “We do still have Ten16, but that’s as useless as a limp dick trying to impregnate a woman.”

Disclosure: Ben Doornbos, who is an accountant and financial analyst at Ten16 Recovery Network, serves on the City Paper’s Board of Directors.

In Midland, all roads seem to lead to the Ten16 Recovery Network. Good or bad, anyone connected to the epidemic had something to say about the organization. At their residential program, they have around fourteen or fifteen people enrolled. At the men’s recovery house, they have twelve and six at the women’s, upon the latest count. At the Recovery Center, around 125 people are engaged in treatment.

ADVERTISEMENT

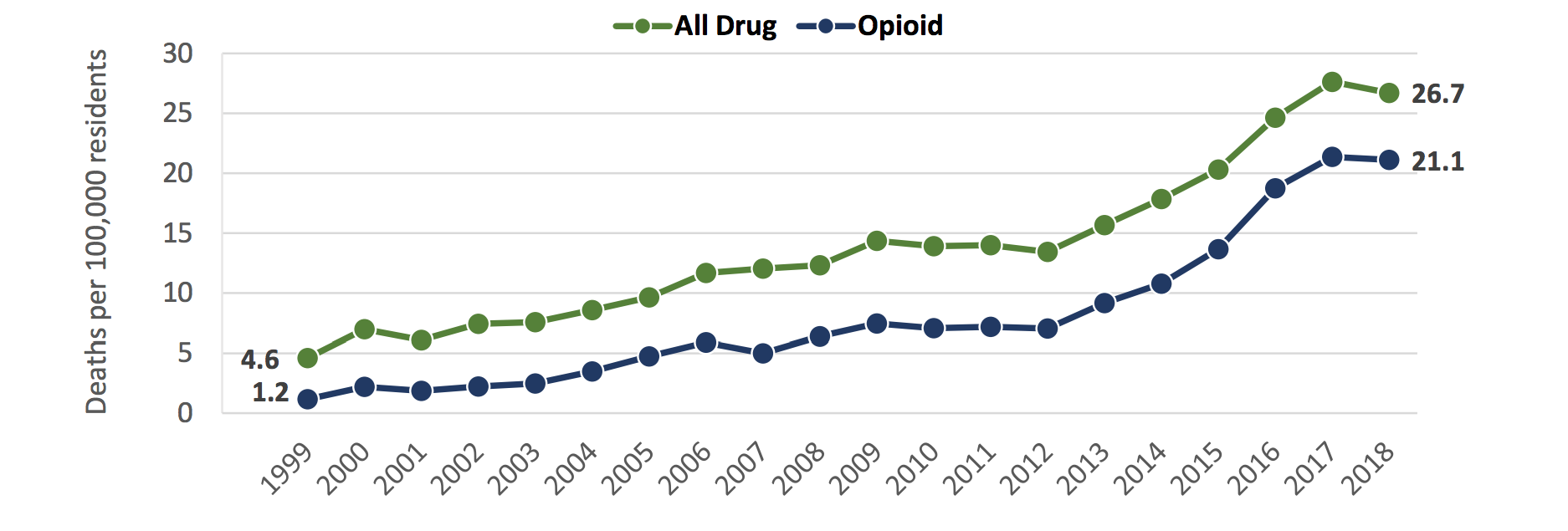

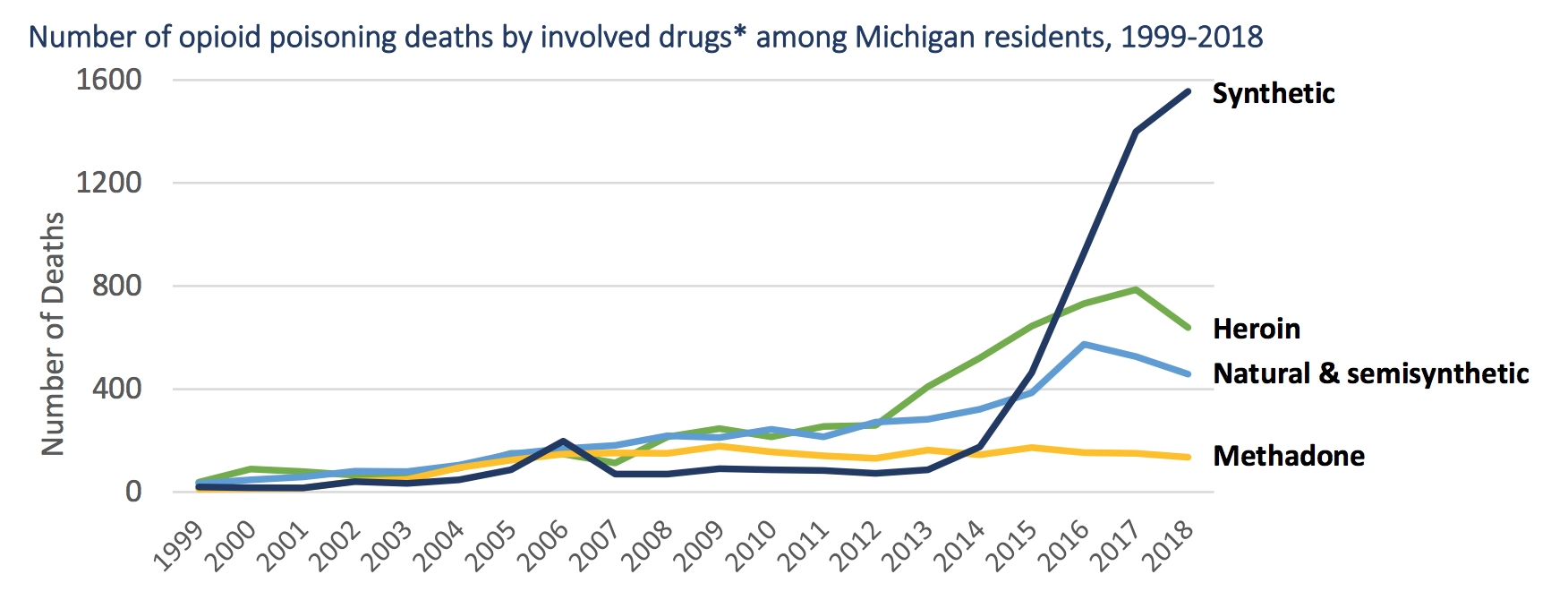

“In the good old days, there used to be just pure heroin. Or heroin cut with other kinds of things that weren’t as lethal as fentanyl could be, just because it’s stronger,” says Sam Price, President and CEO of the Ten16 Recovery Network in Midland. “A lot of people that start out with an opiate disorder, started more through pills than through heroin. And in part because of that they feel that at least I’m getting this pill, I know what’s in it, I know how many milligrams of morphine equivalent is in that. And that may then lead to a physical and psychological dependence and can lead to addiction.”

Because pills are more expensive on the street, the drug of choice decision can become an economic one, Price explains. He says that according to the Chief of Police in Midland, a milligram of morphine on the street was about a dollar. So a 20 milligram pill would cost you $20. However, you could get a hit of heroin for between $5-7.

“So its basic economics if I’m trying to manage my supply and financial resources,” he says. “A good percentage of people that we’ve worked with over the years were already injecting their prescription drugs, so they’ve already kind of crossed over the needle taboo which a lot of people would often say that, ‘I’ll do anything, I’ll snort it, I’ll smoke it, but I’ll never put a needle in my body.’ But sometimes out of desperation or the way that they need to experience that euphoria faster, they kind of cross that barrier. Then it makes it, again, easier to consider something like heroin.”

To a person without any kind of addiction, he says none of that makes any sense. But when someone is really in the throes of that, it’s just a whole different ball game. And in terms of how the neurological pathways within someone’s mind can change, it can lead to some of those chronic practices.

“There’s all kinds of irrational rationalizations – and I think that goes for all of us. Whether it’s my overeating that I’m going to do because it’s a Friday night and it’s been another crappy week, so I’m going to order sixteen wings rather than eight,” he says. “We all rationalize different things in different ways.”

Price has been with the organization since 2003. And in terms of the scope of services in Midland County, they have a detox program, a residential program, a center for recovery wellness which is a combination of outpatient counseling and peer support services. They also have both men’s and women’s recovery houses here in town, as well as a program with MidMichigan Health where they have a staff person embedded in the emergency department.

“We’re actually in eight counties across the Great Lakes Bay Region, in ten emergency departments at this point,” he says. “We have programs at CMU and at Ferris. We’re at twenty different locations providing different levels of services, we do preventions in the schools in Clare, Gladwin, Isabella area. So we’ve got a pretty broad footprint in terms of the scope of services that we offer.”

Some of the other partnerships that they have joined forces with include the Great Lakes Bay Health Services out of Saginaw, where they bring out a mobile medical bus every other week. That way if a client is ever interested in Vivitrol as a medication then they can get it through that facility. “And they don’t have to go to a doctor’s office, they can come right here for that,” he says.

Price and his wife originally grew up in Midland, but were both down in the Lansing area when they met. But they had aging parents, and when the opportunity for Ten16 opened up, it brought them back here in 2003.

“We were pretty small when I got here, but it’s grown considerably since then,” he says.

The Ten16 name has a two-fold purpose, he explains. He says they were originally founded by nine local churches, which opened the Open Door homeless shelter the year before. That ended up triggering some people in the faith community and made them realize that there really wasn’t a facility for somebody trying to rebuild their lives. At the time, it got things rolling and while they were trying to come up with a name, they did a type of focus group with the men living in the halfway house and everyone agreed that they didn’t really want something in someone’s backyard with an obvious addiction center name.

“They said, we really don’t care what you call yourselves, just don’t call it something like ‘new hope recovery house,’ because then everybody knows exactly what’s going on,” says Price. “That was one data point. And at the same time, the churches and the founding board were kind of debating this. And the sheriff at the time, Jim McNutt, happened to mention that they use these numeric radio codes in the communication with the patrol officers, and he mentioned that a 1016 meant that there was an open door at the scene of where the officer was going to go, like it was a burglary scene or something like that. So, how providential that our street address would mean that ‘open door’ and we just opened the Open Door homeless shelter the year before, so we became the 1016 home.”

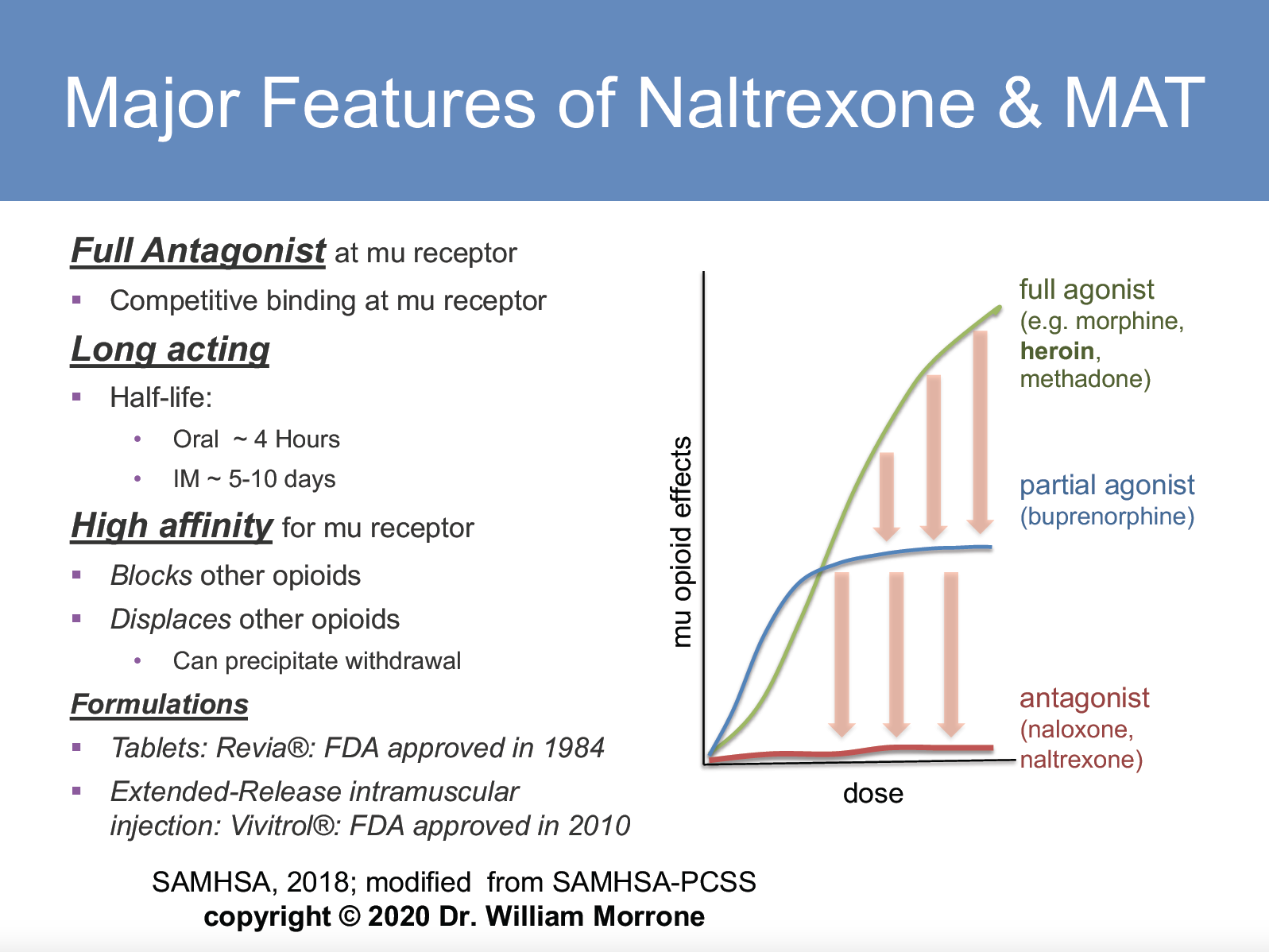

There are four different paths a person can choose when they decide that they want help, says Price. One is that they can just go drug free. The other three require the use of one of three different medication treatments – each one acting as a blocking mechanism from the strongest to the mildest forms: Methadone, Buprenorphine or Naltrexone.

Narcan, Price explains, is a blessing and a curse. It’s what he calls a “rescue drug,” because it’s used when a person is on the verge of death during an overdose. So it’s used almost like a set of cardiac defibrillators, but for your brain.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Thank God we have it, because it (Narcan) has saved many lives,” he says. “But it can cause a false sense of security for some, but we also know that as fentanyl gets carved into it, for some people, it may take three or four doses of Narcan to be administered to get me reversed out. People also don’t understand that it just opens that window for a short period of time – they can go back into that overdose if they’re not careful. So they need to go to the E.R.”

“One of the things about going totally abstinence-based is that the longer I go without using opiates, then my tolerance level changes. So, if I have the unfortunate situation where I have a relapse and I go back to using at the same level that I used to use at, then there’s a much higher potential for having an overdose because my tolerance has changed so much,” he says. “So that’s one of the main reasons for the encouragement for using these medications is to protect against that. Because if I’m on Vivitrol (naltrexone), and I’m pursuing things that way, and I do have a relapse, or an attempted relapse, then I can’t experience any euphoria from that.”

“[The euphoria/high from heroin] I’ve heard described as being wrapped in a nice warm blanket,” says Price. “And it does kind of numb me out. The reason why that’s attractive to so many people has to do with the brokenness within their story. For between 80 to 90 percent of the women who struggle with addiction have a significant history of trauma in their background. And probably about 50 percent of the men have trauma in their background. So, if I have pain and guilt and shame within me because of what was done to me in my early years and on from there… well, if I compare what opiates do for me versus alcohol for example, alcohol is a depressant, which is going to make me feel worse in the long run. And the seductive thing about opiates to that feeling nothing perspective is because I’m so uncomfortable in my own skin, that the euphoria and that numbness that I feel means that I don’t have to feel any of that pain. Because those jagged edges are so sharp inside me, that I don’t know how to live with that. And because of the trauma that I’ve experienced, I’ve never had healthy nurturing relationships to kind of develop the coping skills to know how to move past that, or to somehow grieve and heal from that and move forward in some fashion.”

Price talks a lot about trauma and the “minefield” of problems and emotions that someone must navigate to get to recovery. He states that the hardships that plague a personality that has never properly developed the coping skills to deal with traumatic issues, like death, divorce or loss, have to endure a pretty heroic path to get to that point of sustained recovery.

“That’s why it’s so important for communities to understand what that journey requires, to be supportive of that so that we’re not stigmatizing,” he says. “The more that we can make it okay and safe to talk openly about that struggle, the easier it is for healing to continue to move forward.”

Price says that the flaw behind the old-school Just Say No campaign is that we generally don’t understand addiction.

“We want to think that addiction lives up in the prefrontal cortex of our brain where right and wrong live, which is not the case… instead it’s in the limbic system which is part of the primitive part of our brain that doesn’t have any speech connected to it. So it doesn’t have any ability to verbalize stuff, and it’s completely in an unconscious portion of our brain, so we have no control over it,” he says.

He says that the fundamental driver, if you were to ask most, would be that unlike some of the others (except for alcohol, because alcohol withdrawal is life threatening) is that the absence of opiates is incredibly painful. So, in order to not feel that, an opiate addict will do just about anything to not feel that.

“The best word picture that I’ve ever heard for opiate withdrawal is that it feels like ‘my bones are trying to pop through my skin, and I’ve got razor blades raking down my flesh,'” he explains. “And that lasts for 3-5 days. Well, who wants to experience that? So a lot of people want to think that when they’re chasing the drug, it’s all just to get numb and feel good and cozy and zone out and drool – no. For most of the folks that are in that deep end stage of dependence, it’s really more about not experiencing that withdrawal. Because it’s just so incredibly painful.”

And he says that’s why a lot of people will choose methadone, buprenorphine or naltrexone, because they just don’t want to face that. They’re not going to die, but it feels like they’re going to die, and that’s scary for people.

“That’s what drives some of that real erratic behavior, because they’re just desperate to not feel that way,” he says.

* * *

“There are people that want to say what I say. They can’t because the money that they accept personally in their careers or for their businesses is at risk to admit the things that I say,” Dr. William Morrone, MPH, MS, FASAM, and Medical Director of Recovery Pathways in Essexville, tell the City Paper. “I say things that other people think.”

“The abstinence based recovery community and I are friends. On any given day, we have businesses that compete. At some other level, we’re partners,” says Dr. Morrone. “The federal government comes out with millions of dollars to treat people in medication assisted treatment (MAT). Midland’s group doesn’t do it. I do it. The Midland Daily News goes to them for the interview.”

When asked if that was simply because the Midland-based Ten16 is in Midland and Dr. Morrone’s not in Midland, Morrone countered, “They don’t do it. If I told you Narcotics Anonymous is philosophically against it, why would you go interview somebody that’s against MAT. MAT, supported by the government, is now a funding target to broker change.”

Dr. Morrone says he’s been treating Midland patients for 11 years but he’s still not accepted into the organized general medical community. He says that the quality of his care is evidence-based and he is certified as an addictionologist. He is credentialed by three different licensing bodies for addiction. He employs 18 therapists and works in 8 counties.

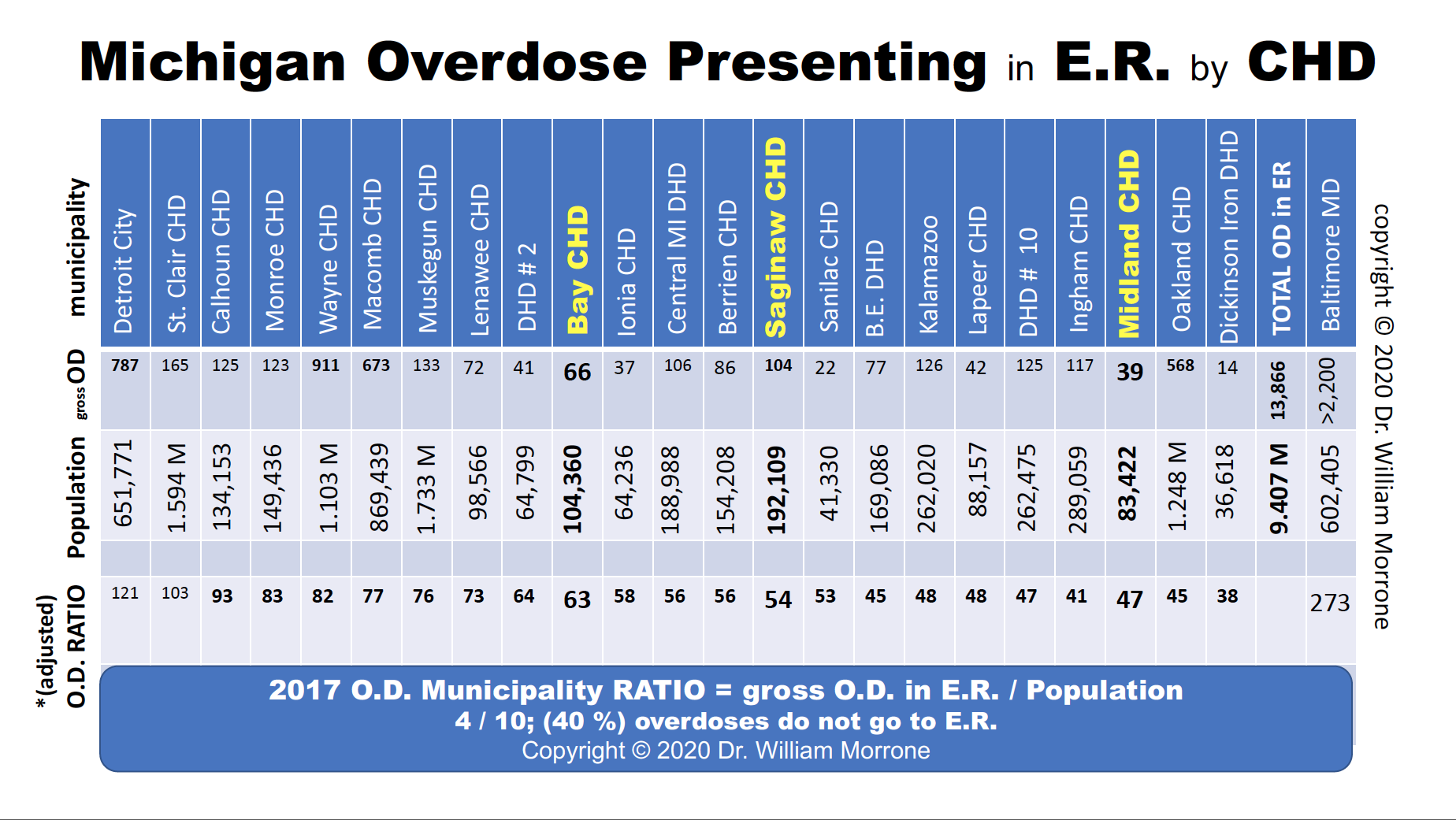

“Nobody can show you an increase in survival,” he says. “Everybody shows you more deaths and the number of pills prescribed. There are 83 counties. No county, generally, is getting better, except two counties – Isabella and Bay. Because they have and embrace Dr. Morrone clinics.”

Dr. Morrone is hoping to compare the Tri-Cities for addiction data and he’s looking for ways to properly access county-specific data.

“We don’t blame anybody. We’re looking for ways to collaborate. It’s dirty laundry that nobody wants to talk about it. Without being honest about the numbers or data, how can we ever fix this?”

“Midland has to recruit teachers, IT, accountants, engineers, scientists, chemists and sales and marketing from all over America to come to a city that the husband or wife doesn’t know has a classic American drug problem,” says Dr. Morrone about the stigma and neglect of an epidemic in the community. “I offered discreet, confidential treatment services (in 2017) through a third-party human resource to a large traditional Midland employer. I was told, ‘our human resources’ is robust and can handle this. Thank you, but, no thank you.'”

‘Opioids,’ he explains, is an umbrella term.

“In American media, they never focus on the fentanyl and heroin issues because they’re illegal. Our culture needs a villain. We are not honest if we only continue to punish the prescriptions and the doctors and we miss funding and energy to treat people properly.”

“There’s 187 medical schools in America. You might have seven or eight that have addiction medicine departments that can teach,” he says. “We have five major hospitals in this area. They should all have an addiction medicine department.”

Dr. Morrone says he’s doing “rural” tele-medicine and jail medicine, because if you really want to stop people from dying, you need to go to the highest risk people.

“The [Midland County] Jail has asked for a program to come and serve their inmates,” he says. “They sent us something and said they want to enter into an agreement and we wrote up a contract, we send somebody over that does a screening, that does some counseling and then we offer them the naltrexone [also known by the brand name Vivitrol] injection. We’re beginning that same program in Bay County. I don’t know what Saginaw is doing. This is such a huge historic step, and I’m not joking when I say that the number one entity delivering treatment for substance use disorder right now in the State of Michigan is criminal justice.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“You’d think there’d be a bunch of guys like me. The biggest problem with addiction treatment is we’re paid so poorly, and were treated so poorly by medical societies and hospitals, that nobody wants to do this,” he says. “But the sheriff asked us to come in and copy the same program we have in other counties there. Now, I think that’s the biggest story – that they are doing a fantastic job.”

Methadone is an opiate that was left over from World War II, he explains. It fills up the brain and at low doses, one would say they (patients) have some relief from pain. What they found was that when they used methadone in New York in the 70s, people stopped shooting heroin. So, because of that, there is an FDA approval to detox with methadone, along with an FDA approval for maintenance – meaning you don’t just detox in 60 days.

That treatment would need to last for an undefined number of years. After the medical community established that this may be dangerous sometimes (for some people), they came up with another drug – buprenorphine.

“[Buprenorphine, also known by the brand name Suboxone] is a partial agonist, which means… if there’s a receptor in your brain, methadone fills that receptor. It slows your breathing down, slows your heart down, takes away some pain, and then while it’s in there, it blocks it. So you’re blocking heroin. But if you take too much methadone, it stays there, and you stop breathing,” he says. “So they come up with buprenorphine, and here’s the difference…”

Dr. Morrone demonstrates each of the three drugs and how they work with two hands: His left hand cupped (to represent a brain receptor) and his right hand into a tight fist (representing methadone) plunged and grasped completely into his cupped left hand. Then he asks this reporter to hit his hands with a small plastic bag lying on the table (representing heroin). Nothing gets into the receptor.

Then, he lifts his right hand about two inches away from the left, not touching each other, and states, this is how buprenorphine works.

“Instead of sitting down in it, and activating it, buprenorphine stops up here – hit it with heroin,” he says.

This reporter repeats his demonstration with the bag. “It still blocks it. Buprenorphine and methadone both block the receptor. But buprenorphine is not as dangerous… they’re both opiates. You just saw that you cannot get heroin into the receptor, that’s how buprenorphine and methadone work.”

“Now, here’s the other thing. Heroin lasts two to three hours. Buprenorphine lasts eighteen.” He grabs a plastic coffee lid and holds it above his cupped left hand. “Now, this is naltrexone. Hit me… it’s a blocker, but it doesn’t occupy the receptor. It’s a lid that sits there, just like these other drugs but it has absolutely no activity. Buprenorphine was a partial, because it went down a little bit, and methadone was a full agonist, because it went all the way to the bottom. But, when you hit me again with the bag [this time with the lid protecting the receptor] you still can’t get in there.”

“When heroin goes in, it gets metabolized and gets kicked out in two or three hours. Naltrexone lasts fifteen hours. Buprenorphine and methadone both last eighteen hours. Naltrexone never slows down the breathing, and you never overdose on this. Buprenorphine slows down the breathing but not as much as methadone. So there’s two activities that you have to remember, and people confuse this,” he says. “The activity caused in the receptor and the occupancy are totally different. Affinity is that occupancy and how tight it is, and you can never, never, never get the heroin in there. But when heroin gets in, you stop breathing and you die. Buprenorphine does not have the same respiratory depression. Because it’s a partial agonist.”

Dr. Morrone explains that as you increase the dose of heroin, you always get an increase in effect, or a “dose response curve.”

“You give more, you get more, you give more, you get more,” he says. “Heroin is the same way. Morphine is the same way. That’s why you die of overdoses of these. You can die of an overdose of methadone too. That’s why it’s not the perfect drug. It has to be regulated, controlled, and if you think about this, methadone for addiction is at MTC [Michigan Therapeutic Consultants] in Mt. Pleasant and Victory Clinic in Saginaw. There are only two clinics you can get it at. They have 300-400 patients each. You cannot get that methadone MAT from any doctor because the federal government makes it special because it may be too dangerous to be put in the hands of fools.”

“Now this green line is methadone. This blue line, is buprenorphine,” he says, referring to FIGURE B. “At some point, you have activity and then at a certain point which is between 40 to 50 percent effective, as you increase the dose, the effect never changes. This is a special name in science called the ceiling effect. You hit the ceiling and then it stays the same. At this dose of buprenorphine, you have 40 percent effect on breathing reduction. There’s a ceiling effect, and you can’t overdose on buprenorphine. Now, this red line is naltrexone – no direct effect. There’s nothing happening.”

So, one would think that naltrexone is probably the least popular of the three heroin-blocking opiates? “It’s also the safest,” explains Dr. Morrone. “And that’s why we may put it in the jail first.”

“If they (active users) are not looking for treatment, if they’re not done yet… they’ll never go there (to treatment),” he says, referring to naltrexone. “The whole idea is, you can’t get people to stop using until they’re ready. So, in one graph, I showed you the difference between methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone. You can occupy the receptor, but it doesn’t mean you activate it.”

Dr. Morrone’s evidence based data driven message is largely this: the majority of active users may not kick heroin on their own or by simply talking through it with peers. They need medication.

The urge to use is so strong and the withdrawal is so painful, there’s no way they can possibly control it by themselves. There are “legacy” services or outreach being provided in Midland County and/or Community Mental Health – neither of which provide medicine (MAT). Community, hospital and political resources have not given Dr. Morrone an even playing field he says.

“I love the Midland recovery resources, but this is where we differ – they believe in 100 percent abstinence from day one. According to evidenced-based data, when you put people into 100 percent abstinence, and say you have a sponsor in a social counseling setting, at 12 weeks, according to evidence-based data, you have 100 percent relapse,” he says.

“At 12 weeks, I’m running 20 percent relapse. The evidence, not Bill Morrone, the evidence, shows hundreds of thousands of people who have been studied for 20 years, prove that with medication (MAT), I can keep you in counseling-treatment and I can improve your drug screenings. Less people die. You stay out of jail, get a job and become a better parent and spouse.”

“So, when you look at the new governor, and you look at what Obama and Trump have both done from Washington D.C., they’ve said it’s time to use evidence-based data, not tradition.

This is really important,” he says. “Look at who has the money, it’s all been given here [to abstinence based-programs] for the last ten years. Guys like me come out and put up a clinic. I’m not on the radar for direct State of Michigan grants. Hospitals don’t underwrite my clinics. The United Way doesn’t grant my clinics money. Foundations do not award me money. Support goes to the non-evidence based programs, because according to tradition, that is what they know. Nothing changes if nothing changes.”

* * *

“We got blindsided, so we had to learn real fast,” LuAnn Wagner tells the City Paper. “Unless you have had to deal with it, you really don’t get it.”

Mrs. Wagner is the mother of Ken Wagner. Ken overdosed on heroin several years ago and is now confined to a wheelchair. He was a closet addict with a problem that extended beyond drug use – it caused him to steal from his fiancee, lie to his family and lose friends he’d known for years.

Though this sounds like a preachy public service announcement, it’s hardly that. Today, Ken needs around the clock care, and its not only a lifestyle shift for him, but for his family.

“How it has changed our life, and what we thought our life would be at this point, are two different things,” she says. “You know, where we thought we would be in our retirement and doing some of the things that we enjoy doing, and here we have a handicapped son… I mean we can’t take off, I mean we can go for awhile, but really I don’t like being gone for long.”

Today, Mrs. Wagner has two part-time jobs. She used to run a nail salon in Midland, but now she does manicures and pedicures from home because of Ken’s condition. She is also a skin-care consultant, which she says helps supplement for some of the other needs Ken doesn’t get money for.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ken is 35, the youngest of her three sons. And what LuAnn didn’t know was that over the years, he had dabbled in drugs since he was a teenager.

“It started in 2000, the year my dad died. And my kids took it very, very hard. And I didn’t realize Ken was that bothered with it. And you don’t realize these things, at the time… and at the time he didn’t get into heavy drugs like shooting heroin until he was probably 16 or 17,” she says.

LuAnn says Ken was a ‘super-smart’ person with an affection for music. He loved the arts, and fit in well with that group of people. She says she only knows about his drug use at such a young age because he used to tell her about it during clean times.

2008 was Ken’s first major overdose. LuAnn was at her mother’s for her 80th birthday in North Carolina. Ken was on his own at the time, but he would come in and clean the nail salon after hours. She had even talked to him the evening before because he wanted to wish his grandmother a happy birthday. Then, at 6 am, she received a frantic phone call from one of her other sons saying that he had overdosed last night and that he was in the hospital.

“That’s how we found out we had an addict,” she says. “After that happened and we had time to reflect, then we figured out, and we’re looking back at things like, ‘okay, that makes sense.’ We just couldn’t understand the behavior sometimes.”

So they got a flight back home and made their way to the hospital in Midland. The nurse on duty had given her a list of things that were wrong with Ken and told the family she didn’t think she would see him alive again by her next shift.

“She figured he would be dead, because he was in such bad shape in the morning,” she says. “That time, he shot up with heroin laced with fentanyl. The reason we found out that – it happened to be since Ken was there so late, he had the lights on and luckily he had the door unlocked… and the police stopped and looked through the window, and they saw somebody laying on the floor. So they walked in and found the needle in his arm. And they were able to test the needle.”

They could also tell because he had hit his head, and when fentanyl gets into someone’s bloodstream, it knocks them out instantaneously – they don’t have time to brace themselves, react or take the needle out of their arm.

“We know he had talked to his girlfriend around 11 pm that night, and the police found him roughly around 5 a.m.,” she says. “He was in a pool of blood and vomit. Luckily, he had not aspirated, because a lot of times that’s what gets people… and luckily he was laying on his side and not his back. He still had a pulse and they of course took him into the hospital.”

Because Ken had been lying motionless on his side for so long, one side of his body was left without circulation, so he had to go through physical therapy for a few weeks after he regained consciousness, LuAnn says.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He said he was done with drugs, he was never doing them again, ‘Mom, I hit rock bottom, I don’t wanna live like that,’ you know, I mean, and I think he meant that, I think he felt that,” she says. “But you don’t know what triggers people when they go back out into the world. And that is a huge problem that Midland has. I talked to Judge Beale about this, in fact. When someone overdoses, you take them to the hospital and there’s help. When you turn them out in the cold, you send them home and it’s usually to families that have been through so much that they don’t want them living with them, because they don’t trust them. [And it] becomes babysitting an adult child.”

LuAnn says on top of hospitalization, Ken also had to face drug charges and go to jail. A few months later, she explained that he got into more trouble by stealing from his girlfriend’s mother around Christmastime. In fact, she says a lot happened in between 2008 and 2011, from more drug charges, to toxic relationships with girlfriends, to jail, to drug court, to relapses – and it took a major toll on the family. Especially LuAnn.

She recalled going to a family Christmas gathering where everyone was laughing, and opening gifts and having a great time, and all she could think about was what she had to do earlier in the day: drop money off in Ken’s commissary at the Midland County Jail.

“It was Christmas, and it was cold… and he didn’t even have underwear,” she says. “And then I’m at this party and it just feels like the world should be stopping instead.”

The Day The World Really Stopped – June 1, 2011

“Ken was participating in drug court, with Judge Beale. And he was actually doing pretty well,” says LuAnn. “He also had this girlfriend who was an addict and supposedly clean. And it took me years to understand the personality… but he was trying to stay clean, and he kept trying to break up with her. And she wouldn’t leave him alone.”

Ken also didn’t have a license, so he depended on a lot of friends to drive him around, she says. At the time, while he was living with this girl, and he had to “drop,” or do a urine test. He dropped clean. He walked across the street from the courthouse to the Ten16 office where they did outpatient services and he had a meeting.

“Now, he doesn’t even remember if he made it to the meeting or not,” she says. “And this is where it gets kind of sketchy, because he doesn’t even remember that part of the afternoon, or when he started taking Xanax that day.”

She explained that they have a lot of hoops to jump through, courses to take, meetings to attend and papers to get signed stating that they’ve been to said meetings. “But he didn’t care. He did what he had to do to stay out on the street, and not go to jail.”

At some point in the day, Ken started taking Xanax, and she says she didn’t know the dosage. But she and her husband were having a nice day. They were celebrating their anniversary, so they had family visiting, and were having a nice evening.

“Ken shows up around 8:30, 9:00, and the minute he walked in the door, I said, ‘Ken what are you on?’ Because I could tell that something was going on. He said, ‘Mom, I just took my nighttime meds early, I wanted to go to bed – it was a frustrating day.’ And I thought, that’s weird, you dropped clean, you said you went to your meeting, how bad could it have been?”

Again, LuAnn says if you asked him today, he can’t remember. So she doesn’t know if he went to the meeting or not or if he was intercepted by the girlfriend before that. She asked him several times but she didn’t like the feeling she had. She says now that she looks back, maybe she should of had him stay at their house.

“I should’ve kicked the girl out and said ‘keep his crap, I don’t care, and don’t ever come back to see us again,’ I mean, I would’ve done anything, if I would’ve known…”

She says they stayed for maybe an hour, but remembers he had to be back to his apartment because he had a curfew.

“So they left, he went back to his apartment, and my understanding is that he took more Xanax,” she says. “Apparently he was spinning around, he wasn’t making sense… I found this out through talking to one of Ken’s friends that the girlfriend had videotaped him coming into the apartment [acting this way] and she’s on the phone videotaping him thinking it’s funny because he’s that high.”

LuAnn says she was never shown the footage, but it’s been described to her by a few of his friends. He apparently went to bed and the girlfriend passed out on the couch watching television.

“Then it wasn’t until a couple hours at least, that she heard him hit the floor and it woke her up. I don’t know if she went in right away or how long he was lying there, but she says he was already turning blue when she found him,” says LuAnn. “So, she called 911, and they came and they gave him four shots of Narcan and that is what brought him back. They said there was no heartbeat, there was no pulse, and the fourth shot is what did the trick.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The doctors told the family that he would never be able to walk, talk or see. That he would never know them and he would just be a vegetable, never knowing anybody. So, the Midland hospital suggested that they pull the plug.

“And I wouldn’t do it. I just couldn’t do it. And I knew that there was something more there,” she says. “I don’t know why, I just remember knowing that that’s not what I should do. So we didn’t. And he did end up understanding, and he still does, understand what is happening. He remembers pretty much everything except for that afternoon and that must’ve been when he first started taking the drugs, and into the evening… he remembers being at our house but doesn’t remember getting back to his apartment. Doesn’t really remember any of that.”

She says the timeline is very jumbled and hazy, because he was in a coma for a few weeks. So an exact order of events or specific details will never be truly known, and time is a concept he has a hard time with now, anyway.

The Xanax is what slowed his heart down enough to stop it. That lack of oxygen and blood to the brain is what caused his permanent brain damage and left him in the state he’s in, LuAnn says. There’s nothing wrong with his eyes, so they plan to donate them when he passes, but the receptors behind his eyes are damaged and limit his vision tremendously. He can see shadows and lights, and he communicates that through a typing machine.

Ken’s mobility is restricted to a wheelchair. He needs help going to the bathroom because he can’t control his bowels. He’s had multiple operations on his feet. The muscles in his jaw are slacked, so he drools and it takes all the effort in the world to smile for a camera. He still enjoys music and the sounds from a television. He gets frustrated, as would anyone, when there’s a misunderstanding or a communication failure. The quality of life for Ken is greatly diminished, but his family, mainly his mother, still holds on.

In a recent staff meeting with Ken’s around the clock care workers, LuAnn broke down.

“I don’t know why, but out of the blue, I said, I hope you people understand, that are new, that Ken will never have a family. Ken will never have a career. He was a gifted artist and musician. And then I started crying… and it just hit me. I mean, I can say the words now and not cry, but at the moment, because Ken is sitting there next to me hanging onto my hand and I feel that life, and I know that that life has been stopped. June 1st, 2011 – his life stopped. The opportunity to move on, to have a family, to have a career, to do anything but sit in a wheelchair or lay in a bed… it just hits you. At that moment, I couldn’t have stopped the tears if I wanted to. Now, I pulled it together and went on with the meeting or whatever, but it’s funny how sometimes it just overtakes you and you succumb to it because otherwise you can’t breathe.”

* * *

To be enrolled in drug court, which in Midland County is a felony drug court, you have to have a pending felony charge. Most often it’s directly related to drug use, either manufacturing, possession or a crime directly related, Deputy Brandan Hodges of the Midland County Sheriff’s Office tells the City Paper.

Deputy Hodges along with another fellow officer, is one of two who take turns serving on the Midland County Drug Court. According to their website, it’s geared toward addressing the needs of non-violent adult felons with substance abuse disorders. Due to local use patterns and associated criminal justice problems the Midland County Adult Drug Court will specifically target individuals between the ages of 18 to 30, whose primary drug of choice is opiates or methamphetamine but all offenders meeting eligibility criteria will be considered.

The Drug Court will focus attention on those individuals whom active addiction is the primary concern. The program will not exclude an otherwise appropriate offender strictly for failing to meet the target population criteria. Admission into the program is subject to the team’s discretion.

The eligibility criteria is as follows:

- Midland County Resident

- At least 17 years old

- Felony charge related to drug abuse or addiction

- Must have a substance abuse/dependence diagnosis

- No history of violent offenses

“To get it in, you have to have a referral from an attorney [their defense attorney], and the attorney has to think that drug court would be an appropriate treatment for you, and also has to be a referral from the prosecutor’s office to say that we think that this is a good course of action for this person, based on those evaluations along with their criminal background and record,” says Hodges. “If there’s someone who’s very violent with gun crimes, generally no, they won’t have a chance to get in.”

Today, the court system no longer calls people addicts because it adds a stigma, he explains. They call them people with a drug disorder.

“We’ve had people successfully complete the program in 14 months, and then I’ve seen others going into their second full year,” he says, stating that there really is no set time frame for a person’s graduation from the program. “So it depends on the steps, how many setbacks they have along the way, the types of treatment that are recommended because it’s more than just an initial 90-day rehab. Somewhere along the line they have needed some additional rehabilitation and in-patient type stuff.”

Sometimes they’re sent to an SAI bootcamp, Hodges explains, because they need a behavioral modification – a big part of this is changing people’s thinking or addictive behaviors.

“Sometimes you have to take some of their compulsivities away and help them to learn to follow rules, so that they can help themselves,” he says.

These are also public hearings and they are held every other Thursday, Hodges explains. The men and women are separated unless there’s a graduation ceremony, then they’re allowed to mix together.

“There’s enough interaction between the males and the females at the different rehabs and group meetings or whatever, and if we don’t minimize that then we get a little extra chatter before or after court, and during court, or some drama… sometimes there’s a boyfriend/girlfriend situation and they feel a little more free to disclose something that might be about a partner or past friend or something,” he explains.

Hodges also says that people don’t get charged when they overdose anymore. “That has been changed. About two years ago that went into effect. It used to be we could get a warrant and do a blood draw and you were technically ‘in possession’ of a controlled substance, because you were – you physically had it and now injected it, and were being held for it,” he says. “But it’s increased a likelihood that someone might not call for emergency services and provide somebody the assistance they need for an overdose because they were afraid of ultimately getting in trouble.”

“But that’s a catch-22, because sometimes someone needs the criminal justice system to rehabilitate them, to force them to take steps that they would otherwise might not have,” he says, also explaining that the drug abuse community has now become pretty cognizant of the fact that there’s no punitive action for an overdose anymore.

* * *

For anybody that might have a Zachary or an Aleisha or a Ken in their family, Terry Hanley has advice.

“Don’t be afraid to get out. Don’t be afraid to ask, don’t be afraid of anything. There’s just so much out there, don’t be afraid to ask for it – whether it’s helping your child who’s an addict or you as a parent to get through it, there’s plenty of help out there,” he says. “And people are there and willing to listen to you. Don’t be afraid of what other people think. We don’t want you to become one of us.”

A.J. Hoffman reports on local business and the arts for the City Paper. He also serves on the City Paper’s board of directors.

I found these stories so very sad, but VERY informative. We need more like this to take the stigma away. People are going to relapse, but it doesn’t mean their programs aren’t working. If Shobe is breaking some rules and you know this for sure, you should take it to the right authorities, not add to the stigma these programs are already fighting.

WAKE UP MIDLAND!!

O am an Advocate for the other side of the problem all the Suicides & deaths by lack of Opiod Meds legal one like norco et 50 million suffer because of our government. way more than addicts! but I have lots of addicts in my family. I wanted to Share a site for the complete cure not bandaid. Go to Seven pillars to total health .com /.org Dr Linda Cheek discovered the cause which has nothing to do with drugs but part of their Brain is toxic & depression they are born with thus. If you follow her formula you will never even desire any drug or Alchohol etc again & be cured. Not expensive not length expensive mind sessions etc! Try it. Doctors of courage.org will lead you to this site as well. you can help thousands of people even before they start! Also go on Law Enforcement against prohibition Jack a Cole will tell you how if prohibition had been lifted as it should have all the poisons in the drugs never would have started & saved 1000’s of lives! these 200k members share this all over the world but our government & Deep pockets make billions of $ off of it all being illegal & on the black market. The propaganda machine. half of the rehab industry hopped on the band wagon for pure greed too in the mea millions BIG Business!!

Went to school with Zach. Was a really good friend of mine at Midland high. He was a great kid. Always making you smile when he thought you needed it. RIP Zach you are missed by many.💔